The Independence Day Of Indonesia

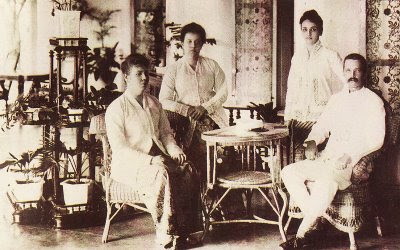

(Members of a Dutch household)

The Rocky Road To Independence Day Of Indonesia, at the beginning of the 20th Century, signs of change were everywhere in the Indies. Dutch military expeditions and private enterprises were making inroad into the hinterlands of Sumatra and the eastern islands. Steam shipping and the Suez Canal (opened in 1869) had bought Europe closer, and the European presence in Java was growing steadily. Gracious new shops, clubs, hotels and homes added an air of cosmopolitan elegance to the towns, while newspapers, factories, gas lighting, trains, tramways, electricity and automobiles imparted a distinct feeling of modernity. Indeed, thousands of newly arrived Dutch immigrants were moved to remark on the extremely tolerable conditions that greeted them in the colonies-that is to say, it was just like home or even better.

But if Netherlands India was becoming increasingly Europeanized, elsewhere in Asia turn-of-the-century modernization was bring in with it a new spirit of nationalism-reflected in the Meiji Restoration and the Japanese victory over Russia (1898), the revolution in China (1911) and the Chulalongkorn reforms in Thailand (1873-1910).

In the indies, nationalism was slow in developing, but just as inevitable. A small but growing number of Indonesians were receiving Dutch educations, and by the turn of the century came the remarkable figure of Raden Ajeng Kartini (1879-1904), the daughter of an enlightened Javanese aristocrat whose ardent yearnings for emancipation were articulated in a series of letters written in Dutch (now published in English as Letters of a Javanese Princess, with a foreword by Eleanor, Roosevelt).

The irony is, from a Dutch point of view, that 19th Century European idealism provided much of the intellectual basis of Indonesian nationalism. As early as 1908, Indonesian attending Dutch schools began to form a number of regional student organizations dedicated to the betterment of their fellows. Though small, aristocratic and extremely idealistic, such organizations nonetheless spawned an elite group of leaders and provided forums in which a new national consciousness was to take shape.

A National Awakening

In 1928, at the second all-Indies student conference, the important concept of a single Indonesian nation (one people, one language, one nation) was proclaimed in the so-called sumpah pemuda (youth pledge). The nationalism and idealism of these students later spread in the print media and through the non-government schools. By the 1930s as many as 130,000 pupils were enrolled in these “wild” (i.e. non-government) Dutch and Malay-medium schools-twice the total attending government schools.

But if Netherlands India was becoming increasingly Europeanized, elsewhere in Asia turn-of-the-century modernization was bring in with it a new spirit of nationalism-reflected in the Meiji Restoration and the Japanese victory over Russia (1898), the revolution in China (1911) and the Chulalongkorn reforms in Thailand (1873-1910).

In the indies, nationalism was slow in developing, but just as inevitable. A small but growing number of Indonesians were receiving Dutch educations, and by the turn of the century came the remarkable figure of Raden Ajeng Kartini (1879-1904), the daughter of an enlightened Javanese aristocrat whose ardent yearnings for emancipation were articulated in a series of letters written in Dutch (now published in English as Letters of a Javanese Princess, with a foreword by Eleanor, Roosevelt).

The irony is, from a Dutch point of view, that 19th Century European idealism provided much of the intellectual basis of Indonesian nationalism. As early as 1908, Indonesian attending Dutch schools began to form a number of regional student organizations dedicated to the betterment of their fellows. Though small, aristocratic and extremely idealistic, such organizations nonetheless spawned an elite group of leaders and provided forums in which a new national consciousness was to take shape.

A National Awakening

In 1928, at the second all-Indies student conference, the important concept of a single Indonesian nation (one people, one language, one nation) was proclaimed in the so-called sumpah pemuda (youth pledge). The nationalism and idealism of these students later spread in the print media and through the non-government schools. By the 1930s as many as 130,000 pupils were enrolled in these “wild” (i.e. non-government) Dutch and Malay-medium schools-twice the total attending government schools.

(Opposition to the Dutch found a voice in groups such as these medical students)

(Opposition to the Dutch found a voice in groups such as these medical students)The colonial authorities watched the formation of the Dutch-educated urban elite with some concern. Two political movements of the day provided much greater cause for alarm, however. The first and most important of these was the pan-Islamic movement which hadits roots in the steady and growing stream of pilgrims visiting Mecca from the mid-19th Century onwards, and in the religious teachings of the ulama (Arabic shcolars). What began in Java in 1909 as a small Islamic traders association (Sarekat Dagang Islamiyah) soon turned into a national confederation of Islamic labor unions (Sarikat Islam) which claimed 2 million members in 1919. Rallies were held, sometimes attracting as many as 50,000 people, and many peasants came to see in the Islamic movement some hope of relief from oppressive economic conditions.

The Indonesian communist movement was also founded around 1910 by small groups of Dutch and Indonesian radicals. It soon moved to embrace both Islam and international communism. Many of its leaders gained control of local Islamic workers’ union and frequently spoke at Islamic rallies, but after the Russian revolution of 1917, also maintained ties with the Comintern and increasingly espoused Marxist-Leninist doctrine. The period from 1910 to 1930 was a turbulent one. Strikes frequently erupted into violence, and while at first the colonial government took a liberal view of these rebellious activities, many Indonesian leaders were eventually arrested and moderate Muslim leaders soon disassociated themselves from political activities. The rank-and-file deserted their unions, and while the communists fought on for several years, staging a series of poorly organized local rebellions in Java and Sumatra up through 1927, they too were crushed.

The Indonesian communist movement was also founded around 1910 by small groups of Dutch and Indonesian radicals. It soon moved to embrace both Islam and international communism. Many of its leaders gained control of local Islamic workers’ union and frequently spoke at Islamic rallies, but after the Russian revolution of 1917, also maintained ties with the Comintern and increasingly espoused Marxist-Leninist doctrine. The period from 1910 to 1930 was a turbulent one. Strikes frequently erupted into violence, and while at first the colonial government took a liberal view of these rebellious activities, many Indonesian leaders were eventually arrested and moderate Muslim leaders soon disassociated themselves from political activities. The rank-and-file deserted their unions, and while the communists fought on for several years, staging a series of poorly organized local rebellions in Java and Sumatra up through 1927, they too were crushed.

(The movement for Independence Day Of Indonesia spawned marches and gatherings.

(The movement for Independence Day Of Indonesia spawned marches and gatherings.Despite Dutch intentions to return to Indonesia after the Japanese defeat,

Independence came in 1950)

Independence came in 1950)

Leadership of the anti-colonial movement then reverted to the student elite. In 1927, a recently graduated engineer by the name of Sukarno, together with his Bandung Stud Club, founded the first major political party with Indonesian independence as its goal. Withing two years his so-called Partai Nasional Indonesia (PNI) had over 10,000 members, due in large part to Soekarno’s gifted oratory. Shortly thereafter, Sukarno was arrested for “openly treasonous statements against the state.” Though publicity tried (in Bandung) and then imprisoned, he was later released. A general crackdown ensued and after 1933, Sukarno and all other student leaders were exiled to distant islands where they remained for almost then years. Ringing in their ears as they were sent off was the statement by then Governor-General de Jonge that the Dutch had “been here for350 years with stick and sword and will remain here for another 350 years with stick and swords.” The flower of secular nationalism, it would seem, had been effectively nipped in the bud.

The Japanese Occupation

There was a king of 12th Century Java, Jayabaya by name, who had prophesied that despotic white men would one day rule but that following the arrival of yellow men from the north (who would remain just as long as it takes the maize to ripen), Java would be freed forever of foreign oppressors and would enter a millennial golden age. When the Japanese invasion came, it is not surprising that many Indonesians interpreted this a liberation from Dutch rule.

The immediate effect of the Japanese invasion of Java in January, 1942 was to show that Dutch military might was basically a bluff. The Japanese encountered little resistance and within just a few weeks they rounded up all Europeans and placed them in concentration camps. Initially there was jubilation, but it immediately became apparent that the Japanese had come to exploit the Indies not to free them.

Throughout the occupation all imports were cut off and Japanese rice requisition steadily increased, creating famines and sparking peasant uprisings which were them ruthlessly put down by the dreaded Kempeitai or Japanese secret police.

The Japanese Occupation

There was a king of 12th Century Java, Jayabaya by name, who had prophesied that despotic white men would one day rule but that following the arrival of yellow men from the north (who would remain just as long as it takes the maize to ripen), Java would be freed forever of foreign oppressors and would enter a millennial golden age. When the Japanese invasion came, it is not surprising that many Indonesians interpreted this a liberation from Dutch rule.

The immediate effect of the Japanese invasion of Java in January, 1942 was to show that Dutch military might was basically a bluff. The Japanese encountered little resistance and within just a few weeks they rounded up all Europeans and placed them in concentration camps. Initially there was jubilation, but it immediately became apparent that the Japanese had come to exploit the Indies not to free them.

Throughout the occupation all imports were cut off and Japanese rice requisition steadily increased, creating famines and sparking peasant uprisings which were them ruthlessly put down by the dreaded Kempeitai or Japanese secret police.

(Bung Tomo, an Indonesian hero from Surabaya)

(Bung Tomo, an Indonesian hero from Surabaya)Still, the Japanese found it necessary to rely on Indonesians and to promote a sense of Indonesian nationhood in order to extract their desired war material Indonesian were placed in many key positions previously held by Dutchmen. The use of the Dutch language was banned and replaced by Indonesian. And nationalist leaders were freed and encouraged to cooperate with the Japanese, which almost of them did. All these factors contributed to growing sense of Indonesian confidence.

When it eventually became apparent, in late 1944 that Japan was losing the war, the Japanese began to promise independence in an attempt to maintain faltering Indonesian support. Nationalist slogans were encouraged, the nationalist anthem (Indonesia Raya) was played, the Indonesian “Red and White”flew next to the “Rising Sun,” Indonesian leaders were brought together for discussions and close to 200,000 young people were hurriedly mobilized into para-military groups. By this point there was clearly no chance of turning back.

Revolution: 1945-1950

Before The Independence Day Of Indonesia, on Aug.9, 1945, the day the second atomic bomb was dropped, there Indonesian leaders were flown to Saigon to meet with the Japanese Commander for Southeast Asia, Marshal Terauchi. The marshal promised them independence for all the former Dutch possessions in Asia and appointed Soekarta chairman of the preparatory committee with Mohammed Hatta as vice-chairman. They arrived back in Jakarta on August 14th and the very next day Japan surrounded unconditionally to the Allies. Following two days of debate, Soekarno and Hatta were persuaded to proclaim merdeka (Independence Day Of Indonesia) on August 17th and the long process of constructing a government was begun.

When it eventually became apparent, in late 1944 that Japan was losing the war, the Japanese began to promise independence in an attempt to maintain faltering Indonesian support. Nationalist slogans were encouraged, the nationalist anthem (Indonesia Raya) was played, the Indonesian “Red and White”flew next to the “Rising Sun,” Indonesian leaders were brought together for discussions and close to 200,000 young people were hurriedly mobilized into para-military groups. By this point there was clearly no chance of turning back.

Revolution: 1945-1950

Before The Independence Day Of Indonesia, on Aug.9, 1945, the day the second atomic bomb was dropped, there Indonesian leaders were flown to Saigon to meet with the Japanese Commander for Southeast Asia, Marshal Terauchi. The marshal promised them independence for all the former Dutch possessions in Asia and appointed Soekarta chairman of the preparatory committee with Mohammed Hatta as vice-chairman. They arrived back in Jakarta on August 14th and the very next day Japan surrounded unconditionally to the Allies. Following two days of debate, Soekarno and Hatta were persuaded to proclaim merdeka (Independence Day Of Indonesia) on August 17th and the long process of constructing a government was begun.

The following months were chaotic. News of the Japanese surrender spread like fire and millions of Indonesian enthusiastically echoed the call for merdeka! The Dutch eventually returned, but Holland was at this time in a shambles and world opinion was against them.

The national leaders, too, were hesitant and divided, awed by the swift course of events and undecided whether to press for full victory or negotiate a compromise. The ensuing struggle was this a strange combination of bitter fighting, punctuated by calm diplomacy.

In the end, heroic sacrifices on the battle field by tens of thousands of Indonesian youth placed the Dutch in an untenable position. Three Dutch “police actions” gave the returning colonial force control of the cities, but each time the ragtag Indonesian army valiantly fought back, and to all foreign observers it became clear that the revolution would drag on for years if a political solution were not achieved.

Finally in January, 1949, the United States halted the transfer of Marshall Plan funds to the Netherlands and the UN Security Council ordered the Dutch to withdraw their forces and negotiate a settlement. This done, Dutch infuence in Indonesia rapidly crumbled, and on Aug. 17, 1950-the fifth anniversary of the merdeka proclamation-all previous governments and agreements were unilaterally swept away by the new government of the Republic of Indonesia.

Bookmark/share this article with others:The national leaders, too, were hesitant and divided, awed by the swift course of events and undecided whether to press for full victory or negotiate a compromise. The ensuing struggle was this a strange combination of bitter fighting, punctuated by calm diplomacy.

In the end, heroic sacrifices on the battle field by tens of thousands of Indonesian youth placed the Dutch in an untenable position. Three Dutch “police actions” gave the returning colonial force control of the cities, but each time the ragtag Indonesian army valiantly fought back, and to all foreign observers it became clear that the revolution would drag on for years if a political solution were not achieved.

Finally in January, 1949, the United States halted the transfer of Marshall Plan funds to the Netherlands and the UN Security Council ordered the Dutch to withdraw their forces and negotiate a settlement. This done, Dutch infuence in Indonesia rapidly crumbled, and on Aug. 17, 1950-the fifth anniversary of the merdeka proclamation-all previous governments and agreements were unilaterally swept away by the new government of the Republic of Indonesia.

Post a Comment