History Of Islam In Indonesia

Today I will write about The History of Islam In Indonesia. Islam first arrived in the Indonesian archipelago not through a series of holy wars or armed rebellions, but rather on the coattails of peaceful economic expansion along the major trade routes of the East. Although Muslim traders had visited the region for centuries, it was not until the important Indian trading centre of Gujarat fell into Muslim hands in the mid-13th Century that Indonesian rulers began to convert to the new faith. The trading ports of Samudra, Perlak and Pasai on the northeastern coast of Sumatra-ports that guarded the entrance to the economically strategic Straits of Malacca-became the first Islamic kingdoms in Indonesia. Marco Polo mentions that Perlak was already Muslim at the time of his visit in 1292, and the tombstone of the first Islamic ruler of Samudra, Sultan Malik al Saleh, bears the date 1297.

The dominant sect of Islam in Indonesia during this period was the mystical brotherhood of Sufism. The Sufis were peripatetic mediums and mystics who propagated charismatic traditions of ecstasy, asceticism, dance and poetry. Such of teachings probably accorded well with the existing political and cultural climate of the Hinduized Indonesian courts-whose God-Kings, Brahmin gurus and Tibeto-Buddhist mystics had held sway for many centuries. Perhaps for this reason, the arrival of Islam in Indonesia seems not to have disturbed the social and political structure of these courts, even though Islam, by stressing the equality of all men before God, would seem to be more egalitarian than the caste oriented Indian religions that existed in many form in Indonesian prior to this.

The dominant sect of Islam in Indonesia during this period was the mystical brotherhood of Sufism. The Sufis were peripatetic mediums and mystics who propagated charismatic traditions of ecstasy, asceticism, dance and poetry. Such of teachings probably accorded well with the existing political and cultural climate of the Hinduized Indonesian courts-whose God-Kings, Brahmin gurus and Tibeto-Buddhist mystics had held sway for many centuries. Perhaps for this reason, the arrival of Islam in Indonesia seems not to have disturbed the social and political structure of these courts, even though Islam, by stressing the equality of all men before God, would seem to be more egalitarian than the caste oriented Indian religions that existed in many form in Indonesian prior to this.

(Tombstone of Sultan Malik al Shaleh - the firstislamic monarch)

Trade and Islam

But conversion to Islam in Indonesia was not accomplished on the basis of faith alone-there were compelling worldly benefits to be obtained. Islamic traders were at this time becoming a dominant force on the international scene. They had controlled the overland trade from China and India to Europe via Persia and the Levant for some time, and with the major textile-producing ports of India in their hands, they began to dominate the maritime trade routes through South and East Asia as well. Conversion thus ensured that Indonesian rulers could participate in the growing international Islamic trade network. And equally importantly, it provided these rulers with protection against the encroachments of two aggressive regional powers, the Thais and the Javanese.

To clarify the process of Islamization in Indonesia, and understanding of the basic political and economic structure of the region at this time is necessary. In the precolonial period, there were essentially three important types of kingdoms: 1) the coastal (riverine) states around the Straits of Malacca that produced little food and few trade goods of their own but relied on trade and control of the seas for their existence; 2) the vast inland states on Java and Bali that produced surpluses of rice in irrigated paddies and possessed large manpower reserves; and 3) the tiny kingdoms on the eastern Maluku islands that produced valuable cloves, nutmegs and mace but little food.

All of these kingdoms imported some "luxury" goods from abroad-textiles and porcelains, precious metals, medicines, and gems, to name but a few. The coastal and spice-producing states also needed to import rice. And the trade was not only insular, but involved foreigners as well-principally Indians and Chinese, but also Arabs, Siamese and Burmese.

Many of these trading patterns were the result of physical limitations on the trade itself. Sailing ships were at the mercy of the annual monsoon winds. Sea voyages to and from China or India could only be made once a year in each direction, so that certain ports came to serve as havens and trading emporiums where traders could gather to exchange their goods while waiting for the winds to shift.

To clarify the process of Islamization in Indonesia, and understanding of the basic political and economic structure of the region at this time is necessary. In the precolonial period, there were essentially three important types of kingdoms: 1) the coastal (riverine) states around the Straits of Malacca that produced little food and few trade goods of their own but relied on trade and control of the seas for their existence; 2) the vast inland states on Java and Bali that produced surpluses of rice in irrigated paddies and possessed large manpower reserves; and 3) the tiny kingdoms on the eastern Maluku islands that produced valuable cloves, nutmegs and mace but little food.

All of these kingdoms imported some "luxury" goods from abroad-textiles and porcelains, precious metals, medicines, and gems, to name but a few. The coastal and spice-producing states also needed to import rice. And the trade was not only insular, but involved foreigners as well-principally Indians and Chinese, but also Arabs, Siamese and Burmese.

Many of these trading patterns were the result of physical limitations on the trade itself. Sailing ships were at the mercy of the annual monsoon winds. Sea voyages to and from China or India could only be made once a year in each direction, so that certain ports came to serve as havens and trading emporiums where traders could gather to exchange their goods while waiting for the winds to shift.

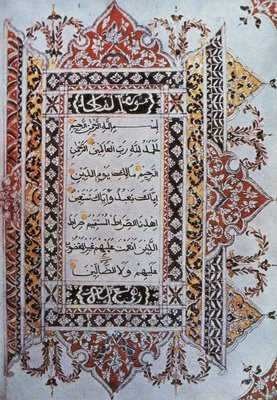

(A page from Koran in Aceh - for more than four centuries a powerful Muslim sultanate)

Conversion of Malacca

Islam received its greatest boost when in 1436, the shrewd ruler of the port of Malacca suddenly converted stay in China. Up to this time, Malacca had been a vassal of China-ruled by descendants of the prestigious Hindus line of Palembang (Sriwijaya) and Singapore kings who had been attacked and evicted by the Javanese and the Thais during the 14th Century. China had proved a valuable patron of Malacca ever since its founding in 1402, but by 1436, China's influence in the region was on the wane, and Thais were once again demanding tribute. By embracing Islam, the ruler of Malacca gained protection against Thai advances. And as a port ruled by a dynasty with a long-standing tradition of catering to overseas traders, Malacca was then in an excellent position to capitalize upon the commercial success of the Islamic world, while maintaining ties with other traders as well. By 1500, Malacca was to become the greatest emporium in the East, a city comparable in size to the largest European cities of the day.

During the 15th Century, all of the trading ports of the western archipelago were brought within Malacca's orbit. The most important of these were the ports along the north or pesisir coast of Java. Traditionally these ports owed their allegiance to the great inland Hindu-Javanese kingdoms, acting in effect as import-export and shipping agents, exchanging Javanese-grown rice for spices, silks, gold, textiles, medicines, gems and other items in a complex series of transaction which vastly increased the original value of the goods. After about 1400, however, the power of the inland Javanese rulers was rapidly declining, and the rulers of the coastal cities were seeking ways to assert their independence and thereby retain more of the profits of the trade for themselves. Gradually, through intermarriage between leading Islamic traders and local aristocrats, relations were cemented with the Muslim world centred at Malacca.

Islam received its greatest boost when in 1436, the shrewd ruler of the port of Malacca suddenly converted stay in China. Up to this time, Malacca had been a vassal of China-ruled by descendants of the prestigious Hindus line of Palembang (Sriwijaya) and Singapore kings who had been attacked and evicted by the Javanese and the Thais during the 14th Century. China had proved a valuable patron of Malacca ever since its founding in 1402, but by 1436, China's influence in the region was on the wane, and Thais were once again demanding tribute. By embracing Islam, the ruler of Malacca gained protection against Thai advances. And as a port ruled by a dynasty with a long-standing tradition of catering to overseas traders, Malacca was then in an excellent position to capitalize upon the commercial success of the Islamic world, while maintaining ties with other traders as well. By 1500, Malacca was to become the greatest emporium in the East, a city comparable in size to the largest European cities of the day.

During the 15th Century, all of the trading ports of the western archipelago were brought within Malacca's orbit. The most important of these were the ports along the north or pesisir coast of Java. Traditionally these ports owed their allegiance to the great inland Hindu-Javanese kingdoms, acting in effect as import-export and shipping agents, exchanging Javanese-grown rice for spices, silks, gold, textiles, medicines, gems and other items in a complex series of transaction which vastly increased the original value of the goods. After about 1400, however, the power of the inland Javanese rulers was rapidly declining, and the rulers of the coastal cities were seeking ways to assert their independence and thereby retain more of the profits of the trade for themselves. Gradually, through intermarriage between leading Islamic traders and local aristocrats, relations were cemented with the Muslim world centred at Malacca.

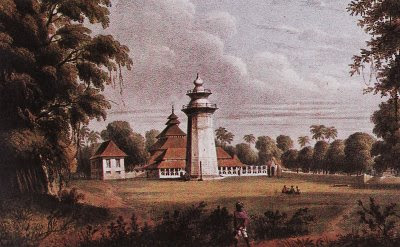

(Print of the historic mosque at Banten -

(Print of the historic mosque at Banten -one of the towns subdued by the Islamic kingdom of Demak)

Islam in Java

If Islamization at first occured peacefully in the coastal kingdoms of Java, a touring point was reached sometime in the early 16th Century when the newly founded Islamic kingdoms of Demak (on the north central coast) attacked and conquered the last great Hindu-Buddhist kingdom of Java. They drove the Hindu rulers to the east and annexed the agriculturally rich Javanese hinterlands. Demak then consolidated its control over the entire north coast by subduing Tuban, Gresik, Madura, Surabaya, Cirebon, Banten, and Jayakarta-emerging as the master of Java by the 16th Century.

The traditional account of Islamization of Java is quite different, but equally intersting. According to Javanese chronicles, nine Islamic saints - the so-called walisanga, propagated Islam through the Javanese shadow play (wayang kulit) and gamelan music. They introduced the kalimat shahadat or Islamic confession offaith and the reading of Korannic prayers to performances of the Ramayana and Mahabarata epics. No better explanation could be given for the origins of Islamic syncretism in Java.

Islam in Indonesia in this period, was the faith of traders and urban dwellers, firmly entrenched in the maritime centres of the archipelago. Many of these towns were quite substantial; Malacca is estimated to have had a population of at least 100,0000 in the 16th Century - as large as Paris, Venice and Naples but dwarfed by Peking and Edo (Tokyo) which then had roughly 1 million inhabitants each. Other cities in Indonesia were comparably large: Semarang had 2,000 houses; Jayakarta had an army of 4,000 men; Tuban was then a walled city with 30,000 inhabitants. Such statistics indicate that the urban population of Indonesia in the 16th Century at least equalled the agrarian population. Thus the typical Indonesia that period was not peasant as he is now, but a town dweller engaged as an artisan, sailor or a trader.

Indonesian cities were also physically different from cities in Europe, the Middle East, India or China. Built without walls for the most part, Indonesian cities were located at river mouths or on wide plains, and relied on surrounding villages for their defence. An official envoy from the Sultanate of Aceh (in north Sumatra) to the Ottoman empire, explained that Acehnese defences consisted not of walls, but of "stout hearts in fighting the enemy and a large number of elephants." Indonesian cities tended also to be very green. Coconut, banana and other fruit trees were everywhere, and most of the widely spaced wooden or bamboo houses had vegetable gardens. The royal compound was the center for defence and might have walls and a moat. With perhaps no more than 5 million people in the entire archipelago land had no intrinsic value except what man made of it. Thus in 1613, when the English wanted some land to build a fortress in Makassar, they had to recompense the residents not for the space but for the coconut trees growing there (at the rate of half a Spanish dollar per tree).

During the 16th Century, Islam in Indonesia continued to spread throughout the Indonesian archipelago but the whole system of Islamic economic and political alliances was swiftly overturned in the dramatic conquest of Malacca in 1511 by a small band of Portuguese. Though the Portuguese, as we shall see, were never able to control more than a portion of the total trade in the region, the capture of Malacca itself had far-reaching consequences. Never again was an Islamic state able to exert the sort of regional infuence once exercised by Malacca. Instead, a number of competing Islamic centers vied with each other and with the Eurepeans for the trade, with the end result that the Dutch were eventually able to divide and conquer almost all of them.

If Islamization at first occured peacefully in the coastal kingdoms of Java, a touring point was reached sometime in the early 16th Century when the newly founded Islamic kingdoms of Demak (on the north central coast) attacked and conquered the last great Hindu-Buddhist kingdom of Java. They drove the Hindu rulers to the east and annexed the agriculturally rich Javanese hinterlands. Demak then consolidated its control over the entire north coast by subduing Tuban, Gresik, Madura, Surabaya, Cirebon, Banten, and Jayakarta-emerging as the master of Java by the 16th Century.

The traditional account of Islamization of Java is quite different, but equally intersting. According to Javanese chronicles, nine Islamic saints - the so-called walisanga, propagated Islam through the Javanese shadow play (wayang kulit) and gamelan music. They introduced the kalimat shahadat or Islamic confession offaith and the reading of Korannic prayers to performances of the Ramayana and Mahabarata epics. No better explanation could be given for the origins of Islamic syncretism in Java.

Islam in Indonesia in this period, was the faith of traders and urban dwellers, firmly entrenched in the maritime centres of the archipelago. Many of these towns were quite substantial; Malacca is estimated to have had a population of at least 100,0000 in the 16th Century - as large as Paris, Venice and Naples but dwarfed by Peking and Edo (Tokyo) which then had roughly 1 million inhabitants each. Other cities in Indonesia were comparably large: Semarang had 2,000 houses; Jayakarta had an army of 4,000 men; Tuban was then a walled city with 30,000 inhabitants. Such statistics indicate that the urban population of Indonesia in the 16th Century at least equalled the agrarian population. Thus the typical Indonesia that period was not peasant as he is now, but a town dweller engaged as an artisan, sailor or a trader.

Indonesian cities were also physically different from cities in Europe, the Middle East, India or China. Built without walls for the most part, Indonesian cities were located at river mouths or on wide plains, and relied on surrounding villages for their defence. An official envoy from the Sultanate of Aceh (in north Sumatra) to the Ottoman empire, explained that Acehnese defences consisted not of walls, but of "stout hearts in fighting the enemy and a large number of elephants." Indonesian cities tended also to be very green. Coconut, banana and other fruit trees were everywhere, and most of the widely spaced wooden or bamboo houses had vegetable gardens. The royal compound was the center for defence and might have walls and a moat. With perhaps no more than 5 million people in the entire archipelago land had no intrinsic value except what man made of it. Thus in 1613, when the English wanted some land to build a fortress in Makassar, they had to recompense the residents not for the space but for the coconut trees growing there (at the rate of half a Spanish dollar per tree).

During the 16th Century, Islam in Indonesia continued to spread throughout the Indonesian archipelago but the whole system of Islamic economic and political alliances was swiftly overturned in the dramatic conquest of Malacca in 1511 by a small band of Portuguese. Though the Portuguese, as we shall see, were never able to control more than a portion of the total trade in the region, the capture of Malacca itself had far-reaching consequences. Never again was an Islamic state able to exert the sort of regional infuence once exercised by Malacca. Instead, a number of competing Islamic centers vied with each other and with the Eurepeans for the trade, with the end result that the Dutch were eventually able to divide and conquer almost all of them.

Muslim traders had a crucial role in expansion of Islam)

Muslim traders had a crucial role in expansion of Islam)The Islamic kingdom of Aceh, at the northern tip of Sumatra, was best situated to benefit from the fall of Malacca. Islamic traders resorted increasingly to Aceh's harbour after 1511, and a succession of aggressive Acehnese rulers slowly built an empire by conquering lesser prots all long he eastern coast of Sumatra. Although repeated attacks on Portuguese Malacca and Islamic Johor were unsuccessful, Aceh nevertheless established itself as the major seapower in the archipelago under the reign of Sultan Iskandar Muda (1607-36). The Acehnese remained powerful and fiercely independent long after that "Golden Age," resisting the Dutch right down into this Century. Now Aceh is one of the most devoutly Muslim regions in Indonesia.

In Java during the second half of the 16th Century, the center of power abruptly shifted from the north coast to an area of central Java near Borobudur, Prambanan and the other Hindu-Buddhist monuments of many centuries earlier. The new kingdom was called Mataram, the name both of the area and the classical Javanese kingdoms once located here. Mataram first conquered Demak; the eastern half of Java and other north coastal ports were subdued by about 1625. Although the Mataram dynasy was Muslim, it patterned itself after the great Hindu-Javanese empires of previous centuries. Court chroniclers traced the lineage of the Mataram line to the deva-rajas of Majapahit rather than to the Islamic rulers of Demak. In fact, the fall of Majapahit to Demak was described in these chronicles as, "the disappearance of the Light of the Universe," rather odd viewpoint for a Muslim writer who describes the demise of an infidel kingdom at the hands of an Islamic saint. Clearly, identification with the prestigious Majapahit royal house was of greater importance than religious solidarity with the coastal powers. And indeed the Islam of the central Javanese courts became an extremely eccentric one - a potpourri of ancient mystical practices, European pomp and Islamic circumstance.

In Java during the second half of the 16th Century, the center of power abruptly shifted from the north coast to an area of central Java near Borobudur, Prambanan and the other Hindu-Buddhist monuments of many centuries earlier. The new kingdom was called Mataram, the name both of the area and the classical Javanese kingdoms once located here. Mataram first conquered Demak; the eastern half of Java and other north coastal ports were subdued by about 1625. Although the Mataram dynasy was Muslim, it patterned itself after the great Hindu-Javanese empires of previous centuries. Court chroniclers traced the lineage of the Mataram line to the deva-rajas of Majapahit rather than to the Islamic rulers of Demak. In fact, the fall of Majapahit to Demak was described in these chronicles as, "the disappearance of the Light of the Universe," rather odd viewpoint for a Muslim writer who describes the demise of an infidel kingdom at the hands of an Islamic saint. Clearly, identification with the prestigious Majapahit royal house was of greater importance than religious solidarity with the coastal powers. And indeed the Islam of the central Javanese courts became an extremely eccentric one - a potpourri of ancient mystical practices, European pomp and Islamic circumstance.

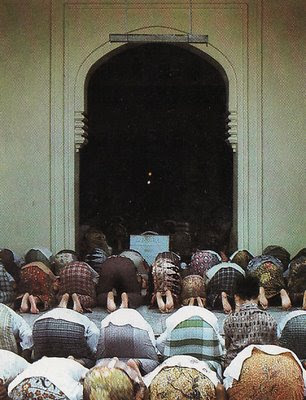

(Worshippers in a mosque)

(Worshippers in a mosque)Islam came to the remaining islands of eastern Indonesia only sporadically. The trading port of Makassar, now the city of Ujung Pandang in south Sulawesi, became an important Islamic center. It expanded rapidly towards the end of the 16th Century. It captured a substantial share of the eastern spice trade for several decades, until it was finally forced to submit to the Dutch in 1667. Makassar in the following way: undecided whether to adopt Islam or Christianity, the Makassarese sent emissaries to both Aceh and Portuguese Malacca to request that religious teachers be sent. The Acehnese, according to this account, simply arrived first.

In the Spice Islands ofMaluku - Ternate, Tidore, Hitu, Ambon and Banda - most of the native rulers converted to Islam fairly early (in the 15th Century) and maintained close ties with first Malacca, then Makassar. However, in the 16th and 17th centuries these kingdoms were brutally conquered by a succession of European powers and those people who survived were then converted to Christianity.

In the Spice Islands ofMaluku - Ternate, Tidore, Hitu, Ambon and Banda - most of the native rulers converted to Islam fairly early (in the 15th Century) and maintained close ties with first Malacca, then Makassar. However, in the 16th and 17th centuries these kingdoms were brutally conquered by a succession of European powers and those people who survived were then converted to Christianity.

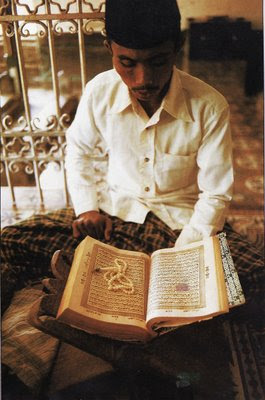

(The Koran receiving this young man's studious attention)

On other islands, Jesuit missionaries arrived even before the Muslims, and together later Dutch Calvinists established many Christian strongholds. Thus most peoples in the eastern archipelago are now either animist or predominantly Christian, and there is a sense in which Christianity put a stop to Islam's eastward a advance in the 17th Century. The Philippines, for example, were colonized and actively converted to Catholicism by Spanish, so that only a few southern islands ever became Islamic. However, in terms of numbers if not geographically, Islam continues to be a growing force throughout the archipelago, with over 80 percent of Indonesians declaring themselves disciples of Mohammed.

Bookmark/share this article with others:

Post a Comment